Obesity is a growing worldwide healthcare problem. But the recently approved weight loss drugs have garnered such popularity and publicity that it is clear these drugs will impact society outside the pharmaceutical and healthcare industries.

One only has to look at some of the recent headlines to see some of the anticipated economic and behavioural changes in the wake of these drugs.

We are also learning that these drugs are having effects that go past lost kilograms. And it is becoming increasingly apparent that we need to better understand what is happening underneath the lost kilos.

In this blog post we will cover the complexity of obesity and weight loss, drug development in this field, and how biomarkers like imaging can help us to better understand metabolic disease.

The complexity of obesity and weight loss

Obesity is a complex disease. Its causes are multifactorial: there is a strong genetic component, but things like dietary patterns, physical activity, and sleep also play important roles. Obesity is also associated with several severe diseases, including type 2 diabetes (T2D), cardiovascular disease (CVD), hypertension, stroke, and cancer, just to name a few. It is through these comorbidities that obesity reduces life expectancy.

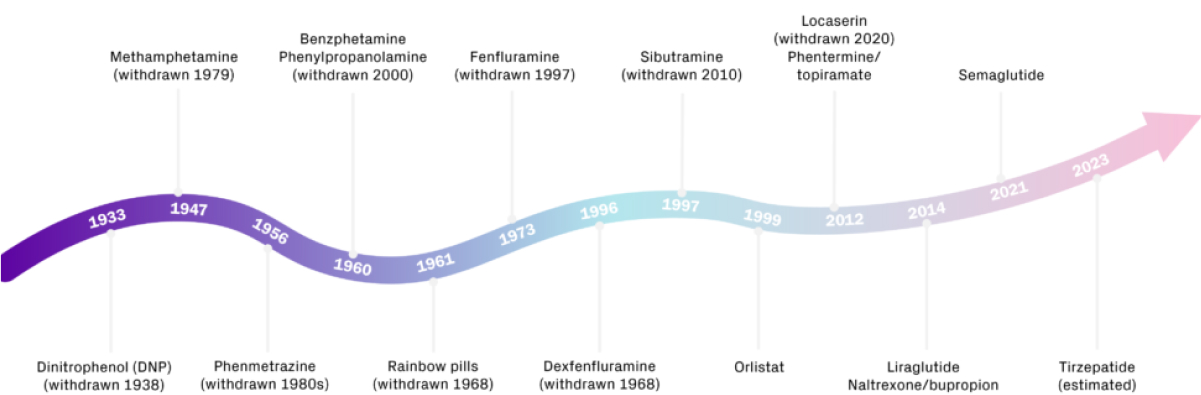

These comorbidities develop over a long time, so to study the effects of obesity requires very large studies with long follow-up times. We also need to find treatments that can offer sustained weight loss over time. Until fairly recently, bariatric surgery has been the only option to give us this long-term weight loss.

The SOS study

The Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) study was designed to look at the effects of bariatric surgery compared to usual obesity care in terms of overall mortality, diabetes, myocardial infarction, and stroke. Around 4000 patients were included, and half underwent bariatric surgery. The study started in the 1980s, so today there is more than 30 years of follow-up data available.

The SOS study showed that there are many different health benefits linked to bariatric surgery. It was associated with reduced overall mortality, and on average life expectancy was improved by 3 years. And in addition to long-term weight loss, bariatric surgery was also linked to reduction in cardiovascular events, reduced overall and female cancer, prevention of diabetes and diabetes complications, diabetes remission, and reduction in end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and chronic kidney disease (CKD). Other research has also found that bariatric surgery was linked to a reduction in adverse liver outcomes. These benefits can be linked to weight loss but can also be independent of it. This tells us, among other things, that we shouldn’t be thinking about treating obesity with a sole focus on inducing weight loss.

It is also worth noting that in the SOS study bariatric surgery was also shown to improve various aspects of health-related quality of life (HRQL), such as social interaction, psychosocial functioning, and depression. They also found that bariatric surgery affected personal relationships. In the treatment group that underwent bariatric surgery, there were more divorces and separations, but also more new relationships.

Weight maintenance and regain

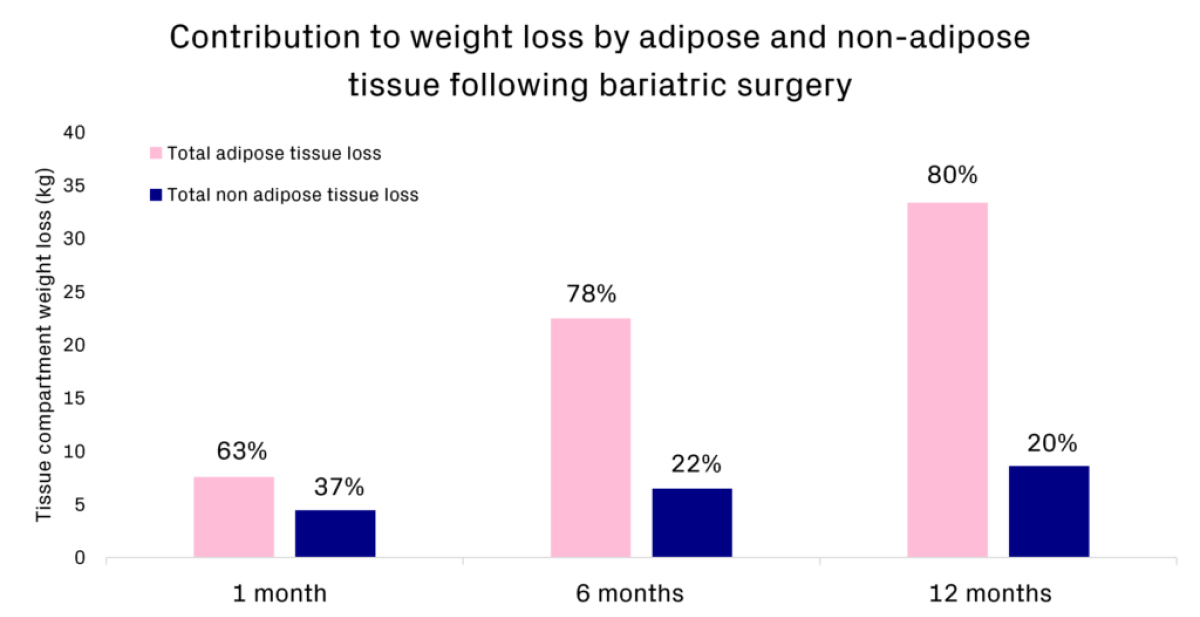

Another interesting aspect of obesity is the concept of weight maintenance and regain. It is common with bariatric surgery that weight is initially lost quickly, with maximum weight loss at approximately 1 year post-surgery, the there is some regain which seems to stabilise around 8 years post-surgery.

This pattern is interesting when we compare it to what we see after other interventions (such as lifestyle advice or previously available weight loss medications), where we typically see weight regain of 0.5 1.0kg per month, normally until almost all the weight has been regained. It has also been shown in a study that followed participants from “The Biggest Loser” competition for 6 years and found that most of the weight regained could be attributed to adipose tissue. This illustrates clearly the idea of a ‘set-point’ that needs to be manipulated in order to see sustained long-term weight loss.

Beyond VAT and SAT, we are also able to use imaging to make more advanced body composition assessments such as muscle volume, composition, and function. A note of caution here – there is currently not a standardised way to do this – some are using thresholds and others are using continuous levels. It is important to keep this in mind when comparing data, we need to pay attention to the method used and how the assessment was done.

We can also, of course, look at end organ effects beyond ectopic fat in the liver, kidney, heart and the brain. There are lots of imaging biomarkers that can be employed based on the research question or specific interest, and depending on what these are, they can potentially be combined to look at multiple organ effects in the same examination. Some examples include:

- In the liver, we can use imaging to non-invasively look at portal hypertension

- In the kidney, we can combine measures of kidney volume and hemodynamics with eGFR to estimate filtration fraction

- In the heart, we can look at myocardial energetics, or altered oxygen consumption

- In the brain, we recently looked at perfusion, glucose uptake and fatty acid uptake. More description of this project is provided below

We used positron emission tomography (PET) to look at the brains of lean controls, individuals that were overweight but without diabetes, and individuals with confirmed type 2 diabetes (T2D). We looked at brain perfusion, glucose uptake, and fatty acid uptake and presented this data earlier this year at EASD 2023.